Transcript: Spanish Moss

Spanish Moss

Native to the southeastern United States and the tropical Americas, Spanish moss, or Tillandsia usneoides, drapes from trees with its long, grey curly strands that hide its occasional flowers. Spanish moss is not really a moss but rather an epiphyte, a plant that grows on trees without harming them. It prefers warm, moist climates, and, interestingly, it belongs to the same botanical family as the pineapple. It prefers live oak or cypress trees but is able to live on other plants and even fences.

It had many uses among Louisiana’s Native Americans, who wove it into a rough cloth for blankets and clothing, made rope, and ignited it on the ends of arrows to gain an advantage in battle. People of the Houma tribe used it to treat fever and chills.

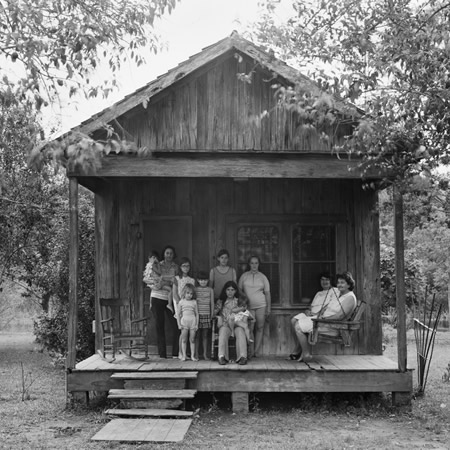

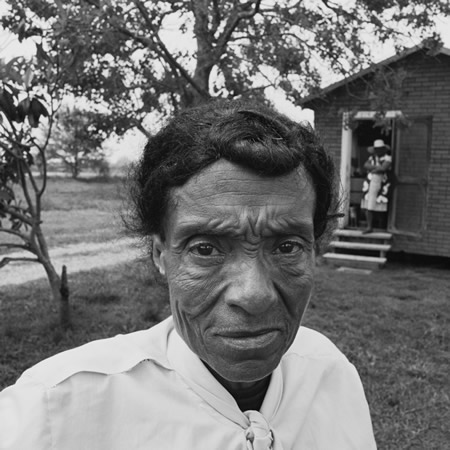

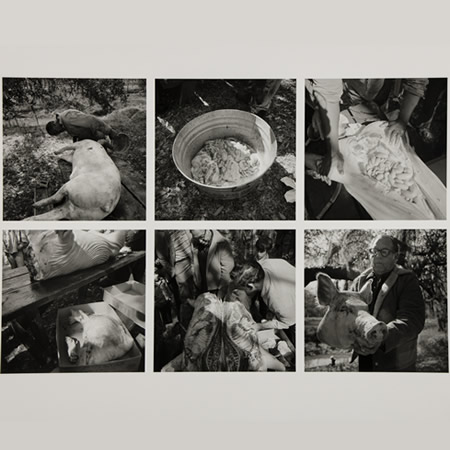

In Louisiana French, the plant is called “Barbe Espagnol,” meaning “Spanish Beard.” Traditionally, Cajuns gathered moss to supplement incomes, since it had a number of commercial applications. Until the mid-20th century, it was used in upholstery in cars and furniture, as well as padding for horse collars and saddles. It provided breathable stuffing, which was very important in the days before air conditioning. First, the plant was harvested from trees using hooked poles. To get to the useful inner filaments of the plant and remove insects, it was cured, and then ginned. Once the inner black strand was exposed, the moss could be cleaned, baled, and shipped. By the time this photograph was taken, commercial harvesting of Spanish moss was on the decline. However, it remains a characteristic part of the landscape.

symbol next to the selected photograph for the corresponding stop. You may also enjoy this guide from anywhere on your mobile device.