During the 1880s and ’90s New Orleans was at the center of the sporting world thanks in large part to prizefighter John L. Sullivan, the “Boston Strong Boy.” Most states prohibited prizefighting in the early 1880s—and though the Deep South was no exception, the region had a reputation for looking the other way when such laws were broken. In February 1882, far-flung journalists and well-heeled fight fans, some of ill repute, descended upon New Orleans in anticipation of a bare-knuckle bout—at an undisclosed location outside city limits—between the 23-year-old Sullivan and world champion Paddy Ryan. On the morning of February 7, the crowd boarded a train bound for the Barnes Hotel in Mississippi City, now part of Gulfport, where a throng of about 1,500 spectators watched the Boston Strong Boy claim the heavyweight title.

Sullivan emerged as one of the nation’s first sports superstars and followed up the Ryan fight with a series of lucrative barnstorming tours, becoming a bona fide celebrity along the way. By 1889 every state in the country had outlawed boxing, forcing Sullivan’s title defense to be clandestine. Sullivan arrived in New Orleans on July 4 to defend his title, stayed at a rooming house on North Rampart Street, and trained at the Young Men’s Gymnastic Club (now the New Orleans Athletic Club). During the summer of 1889, Sullivan reputedly commissioned a plaster cast of his right arm, which usually hangs in the lobby of the New Orleans Athletic Club. Sullivan successfully defended his title at a lumber mill near Hattiesburg in an epic 75-round match with Jake Kilrain. The illegal fight led to arrests for both fighters, compelling Sullivan to vow never to fight bare knuckle again, essentially concluding a brutal era for the sport.

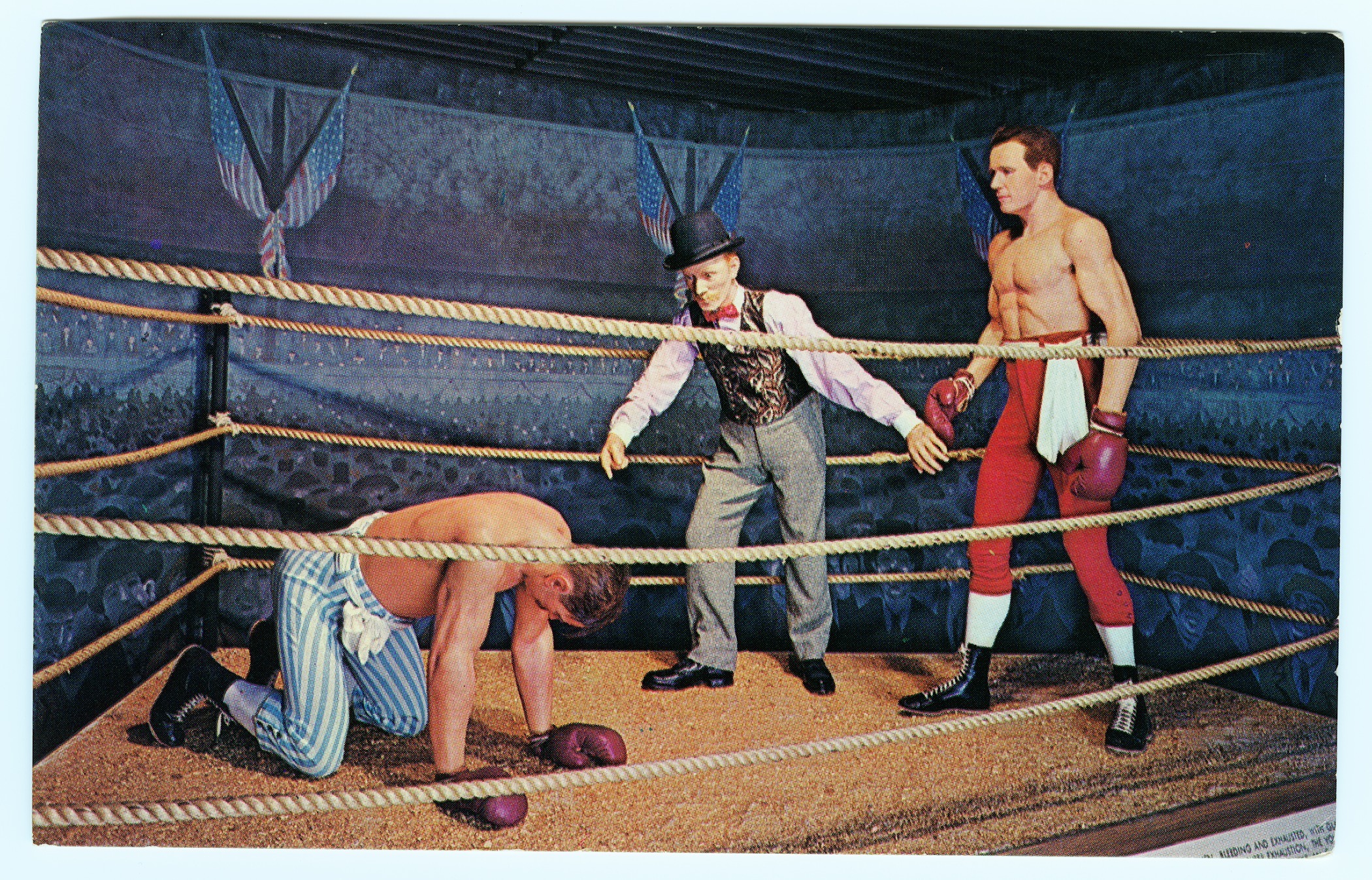

James Corbett finally put an end to Sullivan’s reign in a legal match with gloves at the Olympic Club in New Orleans on September 7, 1892. Sullivan, like many white fighters of his era, refused to compete with black fighters. But one of the fights included in the September 1892 “fistic carnival” at the Olympic Club was the featherweight championship bout between Canadian-born black boxer George Dixon, known as “Little Chocolate,” and white fighter Jack Skelly. The Olympic Club permitted African Americans to watch the fight but required them to enter from a separate entrance and sit in a segregated section. Dixon won the contest easily, and the news of his victory elicited celebrations among African Americans throughout the city.

Education Resources

Click here to browse a souvenir program from the Fistic Carnival—three days of high-profile boxing matches held at the Olympic Club between September 5 and 7, 1892

Click here for an activity about The Olympic Club

The Sullivan-Ryan Prize Fight

February 7, 1882; albumen prints

by Moses and Souby, photographers

The Historic New Orleans Collection, 1978.85.1

The Sullivan-Ryan Prize Fight

February 7, 1882; albumen prints

by Moses and Souby, photographers

The Historic New Orleans Collection, 1978.85.2

George Dixon

ca. 1892

The Historic New Orleans Collection, gift of Nick Ablamis, 98-38-L

Ticket to boxing match between John L. Sullivan and James J. Corbett1892The Historic New Orleans Collection, gift of Mrs. Solis Seiferth, 1986.195.1.1

View of Olympic Club and vignettes of boxersbetween 1950 and 1974The Historic New Orleans Collection, 1974.25.2.40 i-vii

Musée Conti Wax Museum Corbett Sullivan fight postcardca. 1955The Historic New Orleans Collection, gift of Mrs. Charlotte Knipmeyer, 2004.0162.2