Late on April 12, 1803, American diplomat Robert R. Livingston hurried home to his Paris lodgings, sat down at his desk, and began writing one of the most extraordinary letters in American history.

He had just come from a private meeting with French treasury minister François Barbé-Marbois, and needed to report their conversation to his superior, Secretary of State James Madison. “Our conversation was so important,” Livingston wrote near the stroke of midnight, “that I think it necessary to write it while the impressions are strong in my mind.”

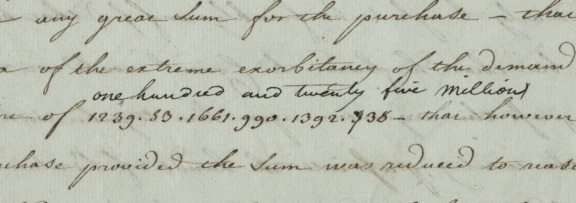

A decoded line of numerals in Robert Livingston's letter reveals France's original asking price for Louisiana. Livingston disguised sensitive parts of his letter to Secretary of State James Madison with a numerical code. (THNOC, 78-56-L)

A decoded line of numerals in Robert Livingston's letter reveals France's original asking price for Louisiana. Livingston disguised sensitive parts of his letter to Secretary of State James Madison with a numerical code. (THNOC, 78-56-L)

Livingston was one of two diplomats sent to Paris by President Thomas Jefferson to negotiate a purchase of New Orleans and its environs from France. The young United States desperately needed to gain control of the Mississippi River’s major port in order to realize the economic potential of its territories west of the Appalachians. Jefferson had dispatched Livingston immediately upon learning that Spain had retroceded New Orleans and Louisiana to their original colonizer, France.

Livingston and his colleague James Monroe were authorized to offer as much as $10 million for New Orleans. Livingston had been frustrated by days of fruitless talks with his French counterparts, but the situation changed at a private meeting on April 12. Barbé-Marbois shared the bombshell revelation that the leader of France’s government, First Consul Napoleon Bonaparte, had read in London newspapers that an expedition of 50,000 British soldiers might be sent to New Orleans. Whether or not the rumor was true, Bonaparte apparently made up his mind to sell not only New Orleans, but the entire 530-million-acre French province of Louisiana to the U.S.

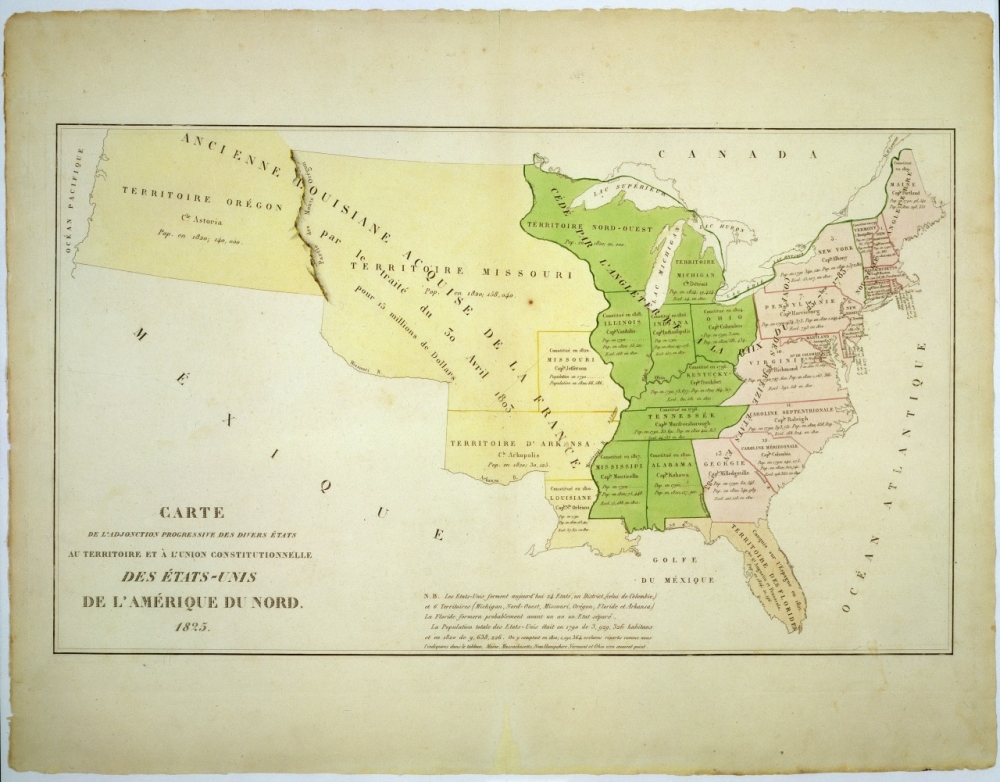

An 1825 map shows the continental United States with the extent of the Louisiana Purchase in yellow. Livingston and Madison intended to purchase only New Orleans, but were able to acquire all of the Louisiana territory. (THNOC, 1970.7)

Bonaparte had recently failed in his attempts to retake the island colony of Saint-Domingue amid the Haitian Revolution, and he knew that the tenuous peace between France and Great Britain might soon collapse. With renewed war in Europe imminent, Bonaparte sought to raise funds for his troops through the sale of Louisiana.

Livingston replied to Barbé-Marbois that Bonaparte’s suggested price of $125 million was exorbitant, well beyond the means of his country to pay, but he understood that he had been presented with a historic opportunity.

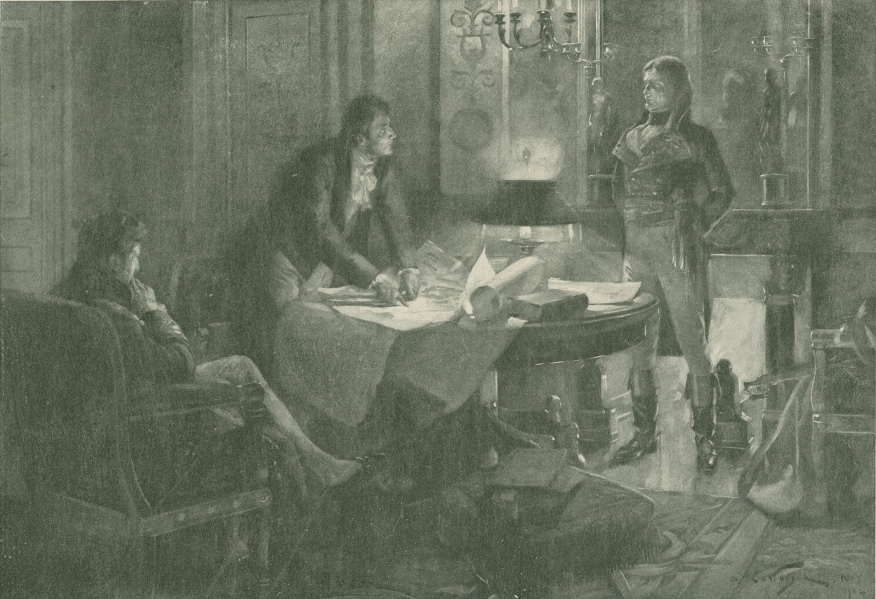

An early-20th-century drawing depicts French diplomat Charles Maurice de Talleyrand (left), Marbois (center), and Bonaparte (right) discussing the terms of the Louisiana Purchase. (THNOC, 1974.25.10.64)

“It is so very important that you should be apprised that a negotiation is actually opened,” he wrote to Madison. “We shall do all we can to cheapen the purchase, but my present sentiment is that we shall buy.” Livingston added that he and Monroe would seek an appointment with Bonaparte later that morning to make an opening offer. He carefully encoded the sensitive parts of the letter, in case it was intercepted before reaching Washington.

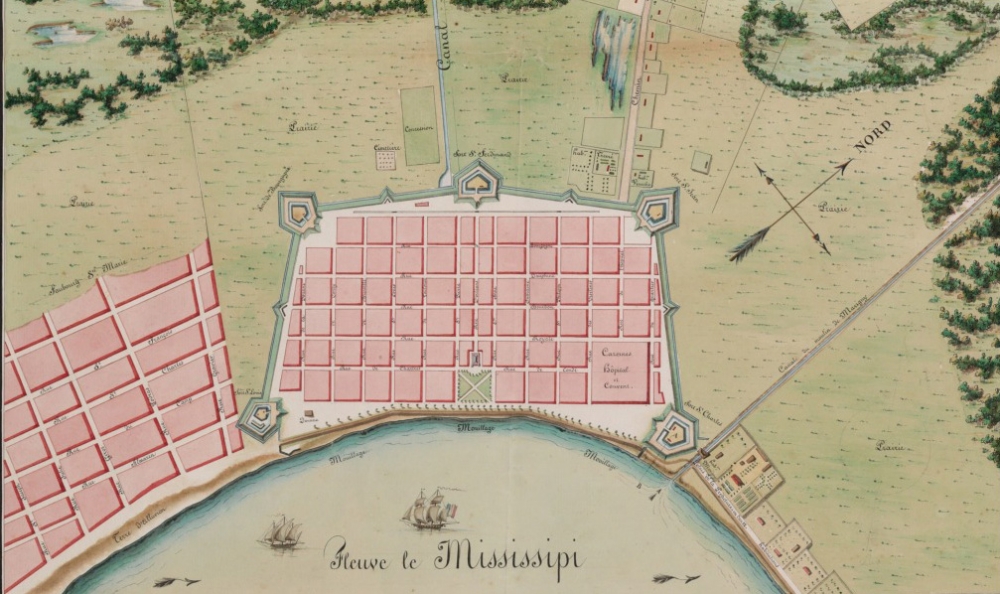

A detail of an 1803 map shows the extent of New Orleans as it would have appeared at the time the U.S. purchased Louisiana. (THNOC, 1987.65 i)

Livingston’s letter hadn’t yet reached his superiors by April 30, 1803, when the deal was completed. He and Monroe had persuaded the French to accept an astounding purchase price of about $15 million—just $5 million more than Livingston had been authorized to pay for New Orleans alone. In one momentous transaction, the U.S. nearly doubled in size, thanks in no small part to the acumen and skill of Livingston, our special envoy in France.

For more, visit THNOC's catalog entry for the letter. A version of this article originally appeared in the Historically Speaking column of the New Orleans Advocate.

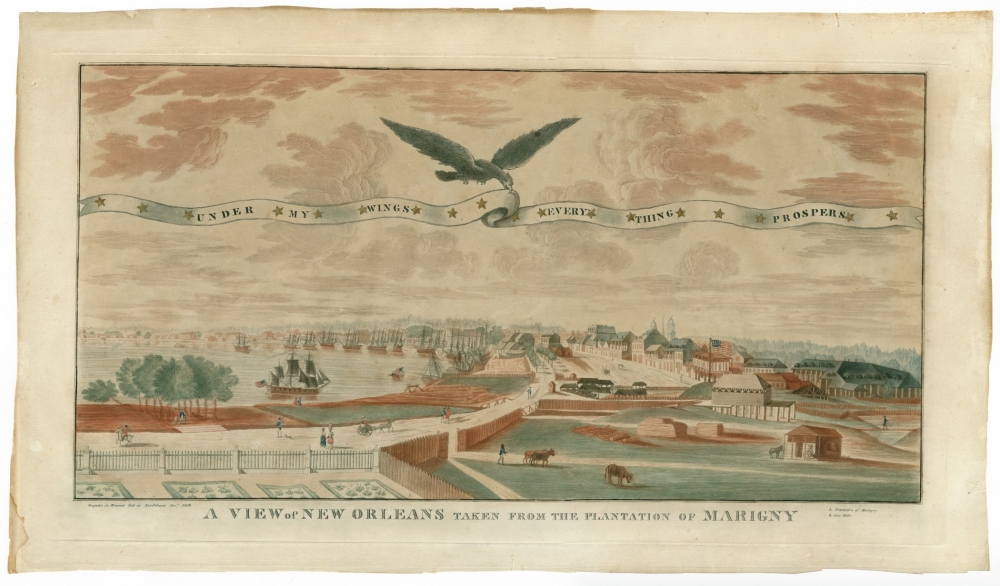

Cover image: A view of New Orleans made months after the Louisiana Purchase depicts an eagle holding a scroll and an American flag. (THNOC, The L. Kemper and Leila Moore Williams Founders Collection, 1958.42)

Cover image: A view of New Orleans made months after the Louisiana Purchase depicts an eagle holding a scroll and an American flag. (THNOC, The L. Kemper and Leila Moore Williams Founders Collection, 1958.42)