50@50

This poster is a reprint of a famous chart outlining everything needed to mix the perfect drink for any time of day. Collins C. Diboll Jr., a prominent New Orleans architect and businessman, designed the chart in 1931, during Prohibition. Diboll graduated from the Tulane School of Architecture in 1926, where he was remembered as a jovial and energetic young man. One biographical sketch described “his love of good food, good friends, and good times,” and his verve certainly was not discouraged by the 18th Amendment. Diboll gave reprints of the charts to his friends over the years and would even frame them under glass trays on which drinks were to be served.

Drawing from his architecture studies, the chart resembles a blueprint, with lines radiating out from the center of a circle in equidistant sections, each of which details the proper ingredients, mixing techniques, glassware, and time of day to make and enjoy a particular drink. If you were in the mood for an Old Fashioned, for example, you’d consult the section titled “Allons au Diable” (an idiom meaning “for the hell of it”). There, a recipe, accompanied by pictures, calls for “[one cube] sugar, [four dashes] bitters, 1 oz whiskey ~ rye or bourbon, 1 lump ice, orange peel and cherry; Serve very cold.” You could then consult the outer edges of the chart for toasts and witticisms about wine and cocktails: “He who drinks a glass a day, will live to die some other way.” A banner bordering the chart depicts people at parties, chefs in kitchens, and various other scenes of enjoyment culture. In the background are well-known emporiums of fine tipple: the Absinthe House Bar, Café de L’Opéra (the French Opera House), the Sazerac Bar, and Henry Ramos’s Imperial Saloon. So the next time the inspiration for a fine cocktail strikes, simply consult Diboll’s chart to find the perfect drink for any occasion.

Embroidery samplers by young girls are well-known artifacts of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, but this one has distinctive features unique to its Louisiana origins. Unlike the outdoor scenes and alphabet rows commonly seen on samplers in England’s thirteen colonies, this one shows Spanish and French influence. The border of the sampler, with the alphabet and the maker’s signature, was a common feature in Spanish embroidery lessons. Similarly, the Catholic church scene hints at young Pauline’s education by the Ursuline nuns of New Orleans. On the altar decorated with flowers and candlesticks, the Eucharist, which Catholics believe to be the body and blood of Christ, is displayed for adoration in a monstrance. Other liturgical paraphernalia are visible on the sides, including an incense censer, a bell, cruets, and a large cross.

For generations, fine needlework was a crucial part of any young woman’s education if she was wealthy enough to devote time and resources to sewing beyond her family’s practical needs. The early New Orleans Ursulines earned a large portion of their operating budget by boarding and teaching the daughters of well-off families, including free people of color. In addition, the Sisters offered daytime catechism classes, and ran the Royal Hospital and an orphanage at the request of the Company of the Indies. The Ursulines’ focus on teaching young women was an innovative mission for an order of nuns. They wanted Louisiana families to be led by good Catholic wives and mothers, and so made sure girls like Pauline were well-informed in their faith. Thanks to the Ursulines’ teaching, colonial New Orleans also enjoyed a high female literacy rate for its time.

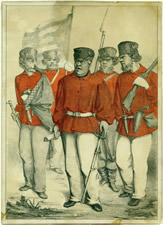

Colonel Bernardo de Gálvez, commander of the Spanish Army’s Fixed Louisiana Infantry Regiment, arrived in New Orleans in December 1776. He almost immediately took office as acting governor of the Louisiana colony on January 1, 1777, upon the departure of Luís de Unzaga. Gálvez was then thirty years old. Despite his youth and inexperience, he effectively dealt with various civil, military, and diplomatic challenges in the Mississippi Valley and northern Gulf Coast, not the least of which was the recently declared war between Great Britain and the colonies that would eventually become the United States.

In 1779, following Spain’s declaration of war on Great Britain, Gálvez led a small force that successfully captured Fort Bute on the Mississippi and Iberville Rivers, as well as British outposts at Baton Rouge and Natchez, effectively ending British control of the lower Mississippi Valley. Gálvez’s subsequent victories in Mobile (1780) and Pensacola (1781) restored Spanish rule in West Florida, and eliminated a British threat to the American Revolution.

Charles III elevated Gálvez to the Spanish nobility and promoted him to the post of Viceroy of New Spain formerly held by his father. For his support of the American cause, Gálvez received the official thanks of the Continental Congress. He remained popular until his death in 1786 at the age of 40.

This beautiful document from a grateful king extols Gálvez’s virtues as a soldier and as a man, and declares him to be the Viscount of Galveston and Count of Gálvez. A detail in Gálvez’s new coat of arms immortalizes Gálvez’s brave entry into Pensacola Bay. The banner on his sailing brig reads “Yo Solo” (I alone), though he had not actually been alone aboard his flagship.

Titled “Our Room” in German, this small watercolor captures a rare snapshot of daily home life in the 1850s French Quarter. The address is today on the 300 block of Dauphine Street, between Bienville and Conti Streets. The language used for the title suggests that the artist may have been one of the many German immigrants to New Orleans in the nineteenth century. His title and cozy domestic subject hint at love and pride for the home his family has built here.

I love using this image in my lectures about decorative arts history because it highlights so many key trends in 1850s material culture. As residences grew larger and industrial advances made possible the mass production of furniture and textiles, more middle-class Americans could afford to set aside a room in their homes as a formal parlor. Families would gather there for entertaining and leisure. With one of the new upright piano models, ladies of the house could offer genteel entertainment with songs and dances.

Almost every object in this room exemplifies its era. The patterned wallpapers, woven carpet, and mantel Argand lamps all resulted from new manufacturing techniques. Large mirrors made rooms feel larger. The display cabinet, or étagère, on the far right was perhaps the epitome of parlor luxury. Valuable more for its stylish form than its storage function, it devoted a great deal of space to showcasing just a few pieces of glass and china.

Even though the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education set the stage for school desegregation in 1954, the process did not actually begin in New Orleans until the fall of 1960. On Monday, November 14, four six-year-old Black girls, accompanied by US marshals for protection, integrated two formerly all-white elementary schools. Ruby Bridges alone attended William J. Frantz Elementary, while Leona Tate, Tessie Prevost, and Gail Etienne together attended McDonough 19.

National media followed the events as they unfolded that November and December, which led to an outpouring of support for the first-grade girls during the Christmas season. In contrast to the verbal abuse that Ruby, Leona, Tessie, and Gail encountered outside of their schools, many sympathizers from across the United States sent Christmas cards offering them love and support. Of the cards on display in the Louisiana History Galleries at 533 Royal Street, I found this one to be particularly touching. The card shows four children of different ethnicities praying together—a simple, beautiful message of kindness and compassion during a dark period in our city’s history. The poem inscribed inside the card also celebrates diversity:

When Christ said,

“Let the children come to me!”

He wanted all children to sit at his knee.

He didn’t say, “Come,

If your skin is light.”

Or, “Come, if the slant

To your eyes is slight.”

For he knew it was not

The tone of the skin

That insured a man’s worth,

But the heart within!

This card touched me on a personal level. My mother was born in Rangoon, Burma, called Myanmar today. When she moved to New Orleans, where I was born, she experienced prejudice because of her ethnicity and accent. Because of her experience, she instilled in me a deep respect for humanity regardless of race and ethnicity. Sixty years after these brave little girls integrated New Orleans schools, it is important to keep their stories alive. I am grateful that The Historic New Orleans Collection has given me the opportunity to engage and speak to our visitors about this momentous event, and to show them the courage found in those four six-year old girls. The message of this card is timeless and powerful, showing goodwill and kindness will always prevail among all peoples.

As a musician, one of my favorite objects in our collection is this military snare drum that belonged to Jordan Bankston Noble (1800–1890), a formerly enslaved veteran of the Battle of New Orleans who volunteered in the 7th US Infantry Regiment. On January 8, 1815, Jordan was fourteen years old. He became a hero on the Chalmette battlefield that day by signaling drum calls as orders were issued by Major General Andrew Jackson. Jackson only spoke English, and several of the soldiers beneath him spoke French or Choctaw. For this reason, Jordan’s signals were of chief importance. In place of Jordan’s drum, shoddy translations may have led to a different outcome.

Jordan Noble didn’t play this drum in the Battle of New Orleans, and we know that because the manufacturer, Klemm & Brother, started importing instruments to the United States in 1816 and opened their Philadelphia storefront in 1819. According to our THNOC database, one New Orleans City Directory lists a Klemm & Brother retail store at 45 Canal Street in 1832. It is likely that Jordan purchased this military snare post-1832 and used it in later battles—perhaps in the Second Seminole War.

I have been building drums for over twenty years, and my favorite component of this instrument is the tuning mechanism—hand-sewn leather straps called “ear hooks” that group each pair of verticals. These are the predecessor of today’s drum keys, and Jordan would have had to pay close attention to their position. I can imagine him kneeling every so often, gently resting his drum on the ground to check the integrity of the hooks. In our year-round humid climate, Jordan would have needed to manipulate these hooks every few hours to check the tension on both drumheads. It would have been a matter of pride to stay in tune—akin to a soldier properly maintaining his weapon.

Jordan continued to play the drum for the remainder of his life, and newspaper records tell us that he was held in high esteem by the New Orleans community after the war. He was called to entertain audiences at the 1884 World’s Industrial and Cotton Centennial Exposition, when he would’ve been eighty-four years old. We have several objects and documents in our collection relating to Jordan Noble, and many of them are available to view in our online catalog. This snare drum stands proudly in our Louisiana History Galleries.

The presidential election of 1828 was the first in which white male Americans who did not own property had the right to vote. This group’s new enfranchisement was expressed by the election of its champion: Andrew Jackson of Tennessee. Jackson had voiced the concerns of poor, everyday Americans four years earlier, but was denied the office despite receiving the plurality of the popular vote. This only fueled Jackson and his supporters to continue fighting, and Jackson spent the next four years campaigning against those he claimed were out of touch with everyday people.

Campaign souvenirs and memorabilia were not new to American elections, but they took on a newfound importance as more and more people were allowed to vote, and Jackson’s campaign knew this well. His supporters produced and marketed everyday items and tools, such as brooches, jacket buttons, wallets, and pitchers, to remind voters of Jackson’s appeal: he was a poor Southerner by birth, a war hero, a frontiersman, and a committed Democrat. This pitcher—copper cast with lusterware, small, not particularly ornate—features an engraving of the future president captioned “General Jackson: The Hero of New Orleans.”

Upon first glance, it seems like an average piece of kitchenware that I’d assume would be found in the home of an average American in the late 1820s, and this is likely intentional: people who would want or use this everyday item were Jackson’s voter base. The message that Jackson saved New Orleans from the British with a ragtag army made up of everyday Americans was one of Jackson’s most brilliant and effective campaign strategies. This perception contributed to the boom in Jackson-related memorabilia long after he had finished running for office.

Amid the conflict between New France and Britain during the French and Indian War, French Acadians living in Nova Scotia were forcefully deported by the English in 1755 after refusing to pledge allegiance to the British crown and renounce Catholicism. Families were split and forced to leave their villages and property behind, leaving many homeless and desperately in search of lost loved ones. This event, commonly known as Le Grand Dérangement, inspired Evangeline, an epic poem written in 1847 by American Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. The poem is known for its depiction of the tragic realities faced by the Acadians following their abrupt expulsion through the fictional story of a displaced Acadian woman. The poem details the scenery of her pilgrimage south and passage along the Mississippi River through Louisiana, where many displaced Acadians, later known as the Cajuns, settled after the expulsion. The poem describes Evangeline’s experiences as she seeks a reunion with her lost love, Gabriel, as well as her impressions of her new environment and longings to return home to her old life in Nova Scotia.

Among THNOC’s holdings relating to Evangeline are an autographed quotation by Longfellow and original hand-drawn illustrations by artist Birket Foster from a version of the poem published in 1892. THNOC also has a 1897 hardcover copy of the poem and numerous related historical resources. Evangeline has become a symbol of the Acadians’ plight after the heartbreak of Le Grand Dérangement and an important emblem of Cajun history and culture.

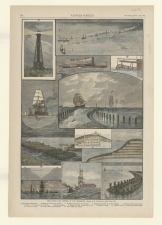

By the mid-1800s a serious problem had formed in the Gulf of Mexico. Over the centuries, the Mississippi River deposited sediment at the mouth of the river, creating sandbars that eventually prevented ships from sailing in and out of the Mississippi River basin. The Corps of Engineers proposed to Congress that a canal be built between the river and Gulf to bypass the sandbars. However, engineer James Buchanan Eads said that jetties, not canals, were the solution to the problem.

If anyone knew the Mississippi River, it was Eads. He first experienced the Mighty Mississippi as a youth in St. Louis while salvaging wrecks on the river. His diving bell invention allowed him to walk along the bottom of the river with an open-ended barrel that had a hose connected to the top, allowing air to be pumped down from a boat; and once at the muddy bottom, all senses relied on touch. He knew the river more intimately than any other engineer, so it seemed odd when Congress rejected his proposal for jetties. After a few years of persuasion, Eads finally made a deal with Congress: he would build the jetties at his own expense, and if they maintained a 30-foot channel, Congress would then pay for the jetties.

Eads wanted to build two parallel piers far out into the Gulf, which would narrow the river and increase its current. The concentrated current would then cut its own channel through the sandbar. So in 1875, two lines of pilings were driven to extend the east and west banks of South Pass, and Eads used willow “mattresses” to build up each jetty wall. These were made of trunks of willow trees that were bound together and stacked. The mattresses were held down with stones and topped with concrete. The crevices were eventually filled with sand and mud as the river flowed past them, rendering the jetties impermeable.

Eads’s jetties were completed in 1879 and maintained a 30-foot channel, eliminating the silt buildup, and opening up the mouth of the Mississippi once again to ships. New Orleans went from ninth largest port in the US to the second largest, just behind New York. This illustration from Harper’s Weekly, published in 1883, shows several views of Eads jetties at the South Pass. The top and center scenes show ships bustling in and around the jetties. Two scenes on the left show cross section views of the 30-foot channel, and several scenes in the lower portion display various perspectives of the willow mattresses.

I have always appreciated the power of cityscapes. These lofty views can reveal the sprawl of a metropolis at a glance, orient the observer within the broader geography, and¬—as unique markers of a place, like fingerprints—inspire civic pride. Before the advent of aerial photography in the late 1850s and early 1860s, however, producing such images required considerable ingenuity from artists. John Bachmann (active 1849–85) was one of many nineteenth-century printmakers who used the bird’s-eye view to illustrate New Orleans’s growth. The perspectives in these artists’ pieces varied: some looked upriver, some downriver, some focused on a narrower slice of the city, and some pulled out for broader vistas. What stands out about this work by Bachmann, who made similar lithographs of many other cities, including New York, Boston, and Philadelphia, is its particularly ambitious scope. Many other panoramic views of New Orleans were cast from realistic vantage points—the top of St. Patrick’s Church was a popular spot—but Bachmann’s gazes out from a contrived position somewhere high above the West Bank, showing most of urban New Orleans along a sweeping curve of the Mississippi River and extending all the way to Lake Pontchartrain on the horizon. Accuracy, understandably, was an issue with many of these bird’s-eye views, though Bachmann’s work is considered relatively faithful for its time. Its most notable distortions can be seen in his emphasis of iconic buildings: St. Louis Cathedral, one hundred seventy feet tall in reality, would be seven hundred feet tall if this image were to scale. Bachmann’s dramatic portrayal of the busy port town, complete with intricately detailed steamboats chugging up and down the river, captured public interest and was reproduced many times in the United States and abroad. Today it provides a fascinating glimpse at the way many people would have imagined the breadth of New Orleans during its rapid expansion in the mid-nineteenth century.

This is a square, printed, blue cloth souvenir bandanna with text that reads “Sugar Bowl ’81” and an image of the trophy that is printed obversely. The Sugar Bowl is an annual college football championship game played in the Superdome in New Orleans. On January 1, 1981, the University of Georgia Bulldogs played against the Notre Dame Fighting Irish. Georgia was undefeated, untied, and—slightly unbelievably—seeking a national championship that year. As ESPN observed of the contest, “The Bulldogs, before former President Jimmy Carter and 77,894 other fans, sought their first national championship.” The Bulldogs won the Sugar Bowl with a final score of 17–10 to finish the season with a record of 12 wins, 0 ties, and 0 losses; Notre Dame finished the season with a record of 9 wins, 2 ties, and 1 loss.

Directories to houses of prostitution in New Orleans's infamous Storyville red-light district are collectively called Blue Books. Storyville—named for Alderman Sidney Story, who sponsored legislation to confine prostitution to a designated part of the city—occupied an area just north of the French Quarter, the site of today's Iberville public housing development. During Storyville's twenty-year existence, from 1898 to 1917, many editions of the Blue Book were issued, listing prostitutes by race and address; however, the guides among The Historic New Orleans Collection’s holdings contain no descriptions of specific sexual services and no fees. They do contain advertisements for other services and products, such as restaurants, quack cures for venereal diseases, liquors, and cigars. Most editions also include a warning that the guides “must not be mailed” because regulations banned the distribution of suggestive materials through the United States Postal Service. Blue Books were sold to men as they stepped off trains at Basin Street or were available in barbershops and saloons. Although many were distributed, authentic editions are scarce today.

Overflowing with groggeries and brothels in the mid- to late nineteenth century, Gallatin Street in the lower French Quarter notoriously found itself center stage for all forms of rioting and debauchery. Wiley Sylvester Churchill’s sarcastically titled ink-on-board depiction of these everyday mass outbreaks identifies the confusion and violence experienced by both patrons and producers. Churchill expressly pairs the wild fervor of the rioters with his own ink strokes and shading, having each pen stroke give ferocious, distinct physicality to the rioters and simultaneously shaping the group as one violent outbreak. While almost none of the subjects’ facial features can be understood, this only emphasizes the brutish nature of certain characters and the unassuming demeanor of the defeated ones. In the center of the image are two assumed prostitutes tugging at each other’s hair and clothes, while just to the right is another woman standing squarely over what appears to be her defeated, male combatant. Just to the left, a man appears to be restraining an oncoming blow from a weapon. Throughout the image’s backdrop, raised and clenched fists shoot up, ready to strike. These images pair humorously with characters such as the man to the far right, sitting with a hand resting upon his cheek, befuddled by the riot behind him. Churchill’s image powerfully displays the wide spectrum of emotions expressed by rioters, both instigators and victims alike, towards prostitution in Gallatin Street.

The focal point of the living room in the Williams Residence is the large circular coffee table. Situated near the middle of the pink and green room, the table—with its dark top, bleached bottom, and glittering gold accents—draws the eye of the visitor. The table was created in the 1940s in the shop of Leila Williams’s designer, Marc Antony, by combining two old objects to make a modern piece of furniture. The top of the table was originally part of a papier-mâché breakfast table. The tabletop, which was made in England around 1850, exhibits all the popular elements of Victorian design. Papier-mâché was a popular material used to make moveable household goods in the mid-nineteenth century, including wine coasters, trays, and breakfast tables. The lightweight pieces were decorated with gold leaf, mother of pearl inlay and painted scenes derived from popular artworks. The central scene on this tabletop shows a queen in renaissance clothing on horseback, surrounded by squires and hunting dogs. It is reminiscent of the popular 1840 romantic painting of Queen Victoria by Edwin Henry Landseer. Depictions of Victoria’s eight castles are featured on the outer rim of the tabletop. The base of the amalgam coffee table is an inverted Corinthian capital that came from a pair of cypress columns salvaged from a nineteenth-century house in New Orleans. The use of cypress is a reminder of the eighty thousand acres of cypress swamps that were the source of the Williamses’ lumber and oil fortunes. The Victorian tabletop and New Orleans capital, two nineteenth-century objects, were melded together to make a piece of twentieth-century furniture. As separate pieces, the papier-mâché tabletop and the cypress columns are reminders of wealth, art, and history, but together they create a modern form emblematic of preservation and mid-nineteenth century design.

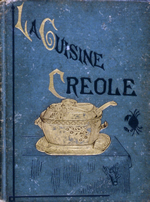

Eccentric traveler and writer Lafcadio Hearn (1850–1904) became fascinated with local culture during the decade he lived in New Orleans, between 1877 and 1887. He wrote numerous articles for the Item and the Times-Democrat newspapers, as well as “Gombo Zhèbes”: Little Dictionary of Creole Proverbs, in 1885, and Chita: A Memory of Last Island, in 1889, the latter about the devastating 1856 hurricane. His 1885 collection of recipes, La Cuisine Créole, was published the same year as the Christian Woman’s Exchange’s Creole Cookery Book. Although neither cookbook was the first to feature Creole recipes, they, along with a section of Will H. Coleman’s 1885 Historical Sketch Book and Guide to New Orleans and Environs—which contained loving descriptions of Creole cuisine—introduced Creole cooking to a wider audience. The books (the publication of which coincided with the 1884–85 World’s Industrial and Cotton Centennial Exposition, held in what is now Audubon Park) established Creole cuisine as a genuine regional treasure.

Dr. George Humphrey Tichenor was a Confederate surgeon during the Civil War. In 1863 his leg was wounded in battle, and for fear of an infection setting in, army doctors wanted to amputate. Tichenor refused, insisting the wound be treated with an antiseptic he had formulated years earlier. Composed mostly of alcohol, with some peppermint oil and arnica, the formula healed the wound and saved Tichenor’s leg, allowing him to revolutionize medical treatments and subsequent surgeries during the war. By 1905, the Dr. G. H. Tichenor Antiseptic Co. was founded in New Orleans. The bottled antiseptic is still sold in drug stores to treat ailments ranging from cuts to sore throats.

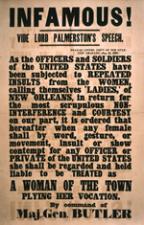

Maj. Gen. Benjamin F. Butler commanded Union troops in occupied New Orleans for seven months during the Civil War, beginning in May 1862. Inhabitants of the fallen city, especially women of society who felt themselves immune to retribution, took every opportunity to insult and ridicule Union officers and soldiers. Exasperated, Butler issued General Order No. 28, popularly known as the “Woman Order.” The decree charged that any woman caught disrespecting one of Butler’s men be treated as a “woman of the town plying her avocation,” implying prostitution. Although the harassment ceased, Butler was denounced by President Jefferson Davis, Confederate generals who read the order to their men, and newspaper editors in the North and the South. Harper’s Weekly printed a cartoon that depicted the situation both before and after Butler’s proclamation. Great Britain’s prime minister, Lord Palmerston, commented in a letter to US Foreign Minister Charles Francis Adams denouncing the order that he could not fully express the “disgust which must be excited in the mind of every honorable man.”